In Conversation with Nin Brudermann

Photo Credit: Blossom Berkofsky

Nin Brudermann is an Austrian artist, born in Vienna, living in New York since her studio Artist Residency at MOMA PS1. Her works are narrative investigations in a variety of media, including film and sculpture as well as performative installations

I had the pleasure of asking Nin about what she considers most significant: the final goal or that the goal holds greater importance. What does she envision the impact this book having on global political discussions and awareness of military history, and so much more

UZOMAH: What, in your opinion, is the most significant message that art can convey to its audience?

NIN: I cannot answer this in terms of a message. What is a message? A message is an intention packaged for delivery. It assumes that the sender knows something that the receiver is missing.

That’s annoyingly didactic. Any art that aims for a message narrows itself down. Art at its rare best can have an effect. A brief connection, a synopsis. It can cause a moment of pause and a minuscule shift of perspective, and that can be life-changing.

U: When considering the commercialization of fine art, how do you approach balancing profit with purpose?

N: I don’t.

U: Do you consider achieving the final goal more significant, or do you find the process of reaching that goal to hold greater importance?

N: I love the onset—the spark, the discovery, the congruence of events. Then the process can become excessively long, and closure a necessity.

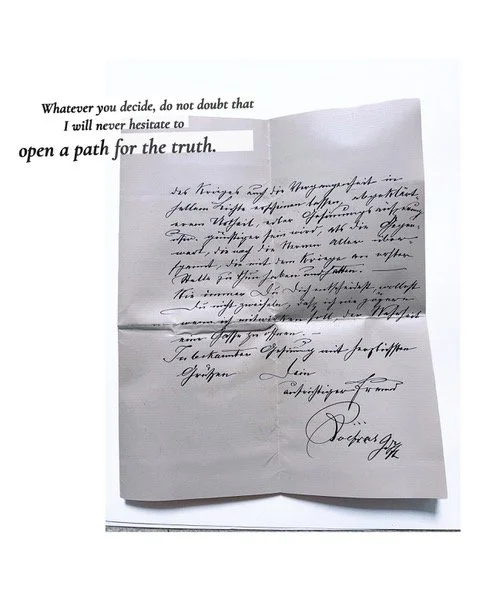

Bolfras to Brudermann [Arthur Baron von Bolfras (1889–1917), Head of the Imperial and Royal Military Chancellery of Austria-Hungary to General Rudolf Ritter von Brudermann, Commanding General of the Third Imperial and Royal Army of Austria-Hungary], (unpublished letter, December 15, 1915) handwritten with overlaid translation, Brudermann family archive, Vienna, courtesy Nin Brudermann.

U: How do the arts help people understand or critique political ideologies?

N: Hopefully, by bringing attention to things/events/thoughts/processes/feelings that had not been considered before, even if it’s just a tilt of perspective. I prefer to work with open processes, also for the viewer/audience, they need to piece it together for an earned revelation, possibly.

Onkel Rudolf, photograph of ‘Uncle Rudolf’, General Rudolf Ritter von Brudermann, c. 1913, Brudermann family archive, Vienna, courtesy Nin Brudermann.

U: Are there any specific questions you wish you could have asked your great-granduncle about those historical documents?

N: I would have asked whether he knew of the top-secret, high-ranking Austrian military meeting of May 18, 1913. A meeting in which it was revealed that the Austrian High Command was acutely vulnerable to Russian kompromat through something plainly simple at the very top: the son of the Austrian Imperial Chief of Staff had a liaison with a female spy.

A meeting that did not end in disclosure, accountability, or reform but in declared loyalty to the Chief. –Yes..

The minutes were ordered destroyed. The matter was to be kept from posterity by all means. In Vienna, no trace of this meeting remained. The only trace would be in Moscow—thanks to Agent 25, a man who had been selling Austria’s military secrets to Russia for years.

One week later, Agent 25 was caught. But instead of being interrogated, instead of being questioned about what had been compromised, whom he had implicated, or who else was involved, he was given a pistol and was ordered to kill himself.

So, to get back to my great-granduncle, I would have asked: Did no one find it extraordinary that this immediate, enforced suicide—ordered by the very man whose own son had just emerged as a security liability—also ensured that no uncomfortable revelations could ever surface?

Gone was the chance to learn what secrets had already been delivered to the enemy.

Gone was the chance to discover what intelligence Austria had failed to receive in return.

Gone was the chance to identify whether Agent 25 was truly the only traitor.

The stakes could not have been higher. Yet the Imperial Chief of Staff did not press the matter. Archduke Franz Ferdinand did: he ordered an investigation into why Agent 25 had been allowed to commit suicide rather than be interrogated. Shortly thereafter, Franz Ferdinand was assassinated in Sarajevo. The investigation was halted. The war began.

And the Chief of Staff—who had pushed relentlessly for war, who is widely regarded as one of the central figures responsible for Austria’s plunge into the catastrophe—remained in command.

So, I would have asked Uncle Rudi: Your Third Army marched forward unaware that the Russian enemy was not merely prepared, but also informed. The Austrian forces were misinformed, outthought, outflanked, and overrun. Did you suspect that the Chief of Staff's failures were not merely strategic? That they were not errors of judgment, but symptoms of something far more dangerous: a culture of blind loyalty to the Chief, which suppressed inquiry when it mattered most?

The “Late Agent 25” who continued feeding secrets to Russia might not have been hidden in some bureau or railway department—but seated at the very top of the General Staff? A father trapped by his son’s indiscretion: the perfect blackmail target.

Sixty-five million troops were mobilized, four empires collapsed, sixteen million lives were lost.

A war had started, whose unresolved causes ensured another would follow twenty-one years later.

Historians still debate why Austria declared war on Serbia: why was the first domino tipped when the consequences should have been obvious to all?

I would have asked Uncle Rudi what he knew.

And I ask where the world might stand now had he not kept his silence.

U: What impact do you envision this book having on global political discussions and awareness of military history?

N: I can only envision a hope: No more blind loyalty to the Chief!

U: Throughout the compilation of the material, which discovery surprised you most?

N: The parts that were missing: those that were physically carved out with a knife. That triggered my interest.

Nin Brudermann, Clash of Giants, 2018, movie poster print, 27 x 40” (68 x 102 cm). Photo Guillaume Ziccarelli.

U: Were there any personal or political challenges you faced during the book's development?

N: I had access to the background machinations of political processes that reshaped the world a hundred years ago. Piecing this together was fascinating.

It became a long process—like so many others, it took years longer than I expected. And yet the parallels to current political challenges stayed uncomfortably close; the material never lost its urgency, unfortunately.

U: Which lessons on humanity were gained from making this book resonate in today’s political climate?

N: The path of humanity is sensitive. If Cleopatra’s nose, to use Jimena Canales’s allegory, had just been a few millimeters shorter, we might not be here today. We shall keep that in mind

U: How would you define an artist’s responsibility to society when creating art?

N: To help look and ask.

U: What obstacles, if any, did you encounter when securing a publisher for the book?

N: None really. Verlag für moderne Kunst has followed the project since its research phase, through the travelling exhibition ‘Notes on the Beginning of the Short 20th Century’, the ‘Clash of Giants’ Film, and the resulting book that details the thread of the film.

For more information about Nin’s artwork and her current publication, please visit her site here. Nin can also be found on Instagram and Facebook. The magazine featured her book; it is available here.