In Conversation with Hilary Harnischfeger

Courtesy of Andrew Schwartz

Hilary Harnischfeger (b. 1972, Melbourne, Australia) earned a BFA from the University of Houston, Houston, TX and an MFA from Columbia University, New York, NY. The artist has been included in exhibitions at Ortega y Gasset Projects, New York, NY; the Fairfield University Art Museum, Fairfield, CT; Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, KS; State University of New York at Purchase, Purchase, NY; the FLAG Art Foundation, New York, NY; MOCA Cleveland, Cleveland, OH; American University Museum at the Katzen Arts Center, Washington, DC; the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY; 80 WSE, New York, NY; Dallas Contemporary, Dallas, TX; Ballroom Marfa, Marfa, TX; Artists Space, New York, NY; and the Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Houston, TX; among others. In 2007, Harnischfeger was the recipient of the Maria Walsh Sharpe Foundation Space Program Award. Her work is in the permanent collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, OH; the Nerman Museum, Overland Park, KS; the Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, NY; and the Fairfield University Art Museum, Fairfield, CT. Harnischfeger lives and works in Brooklyn, NY.

LEA NGUYEN: How has the environment and landscape around you informed your subject matter and/or ideas around your work? Has your upbringing in different places influenced you?

HILARY HARNISCHFEGER: Growing up between very different places taught me to experience landscape as something emotional and embodied. The environments I’ve lived in have shaped my work by teaching me to think of landscape as a record of time, memory, and contradictions rather than just a setting.

For example, in West and Central Texas, the land feels exposed and ancient—evidence of geologic time is visible in the rock, erosion, and vast scale. That sense of deep time made me attentive to layers and permanence, and to how small and temporary human marks can feel in comparison. Houston complicated that view. Its dense vegetation, humidity, flooding, and infrastructure compress time, making change feel constant and cyclical. There, landscape is something negotiated and unstable, shaped as much by systems and climate as by nature.

New York City shifted my focus from horizons to fragments. Space is vertical and interrupted, and the environment is experienced in pieces—through reflections, shadows, and movement—which influenced how I think about compression, rhythm, and layering. Underlying all of this are my earliest memories in Japan, where balance, framing, and the quiet coexistence of nature and structure first shaped my sensitivity to place. Together, these environments inform and ground my work in contrast, temporality, and lived experience of landscape.

Hilary Harnischfeger Harlequin II, 2024 paper, ink, dye, pigment, mica, hydrostone, ceramic, apophyllite, wood, glass 19 1/2 x 14 1/4 x 3 3/4 in (49.5 x 36.2 x 9.5 cm)

L: This body of work is on the largest scale that you’ve created. What was your approach to this process of enlarging? Any similarities and differences regarding process, feelings, and emotions in comparison to smaller-scale works.

H: Working at this scale changed how I approached the work physically and psychologically. The surface stopped feeling like a contained object in front of me and started to feel like a space I was physically inside of. I had to move across it, reach in, step back, and lift instead of making more contained and discrete decisions,

The ideas and materials are similar to my smaller works, but the experience of constructing these pieces on a larger scale felt immersive and exposed—decisions were more visible and harder to undo. At the same time, there’s more freedom. The size allows time, gesture, and chance to show up more clearly than in my smaller pieces. The large scale gave me room to experiment with contrasting larger, saturated areas of color against breaks of negative space, letting the work breathe.

On a smaller scale, the perforations, gaps and punctures—reflect the physical process of geology, with each mark or cut tracing time and sedimentation. Enlarged, these perforations feel more visible, inviting a more direct experience of the surface as volatile, porous, and alive.

L: How has your relationship with the physical labor required evolved?

H: My relationship to physical labor has become more intentional and accepting. Rather than overpowering the materials, I work in conversation with them, allowing complexity to shape my decisions. The carved paper and cast sections of clay and plaster emerge simultaneously, layered and compressed through time and touch. The labor becomes cumulative—each gesture building upon the last—so that the form holds evidence of process, weight, and restraint. What once centered on learning the materials’ technical demands now feels intentional—a slower negotiation between my body and the materials as they settle into balance.

As I’ve worked larger, I’ve learned to pace myself, listen to physical limits, and trust slower progress. The labor now feels less like an obstacle and more like a way of staying present—allowing time, movement, and fatigue to register visibly in the work.

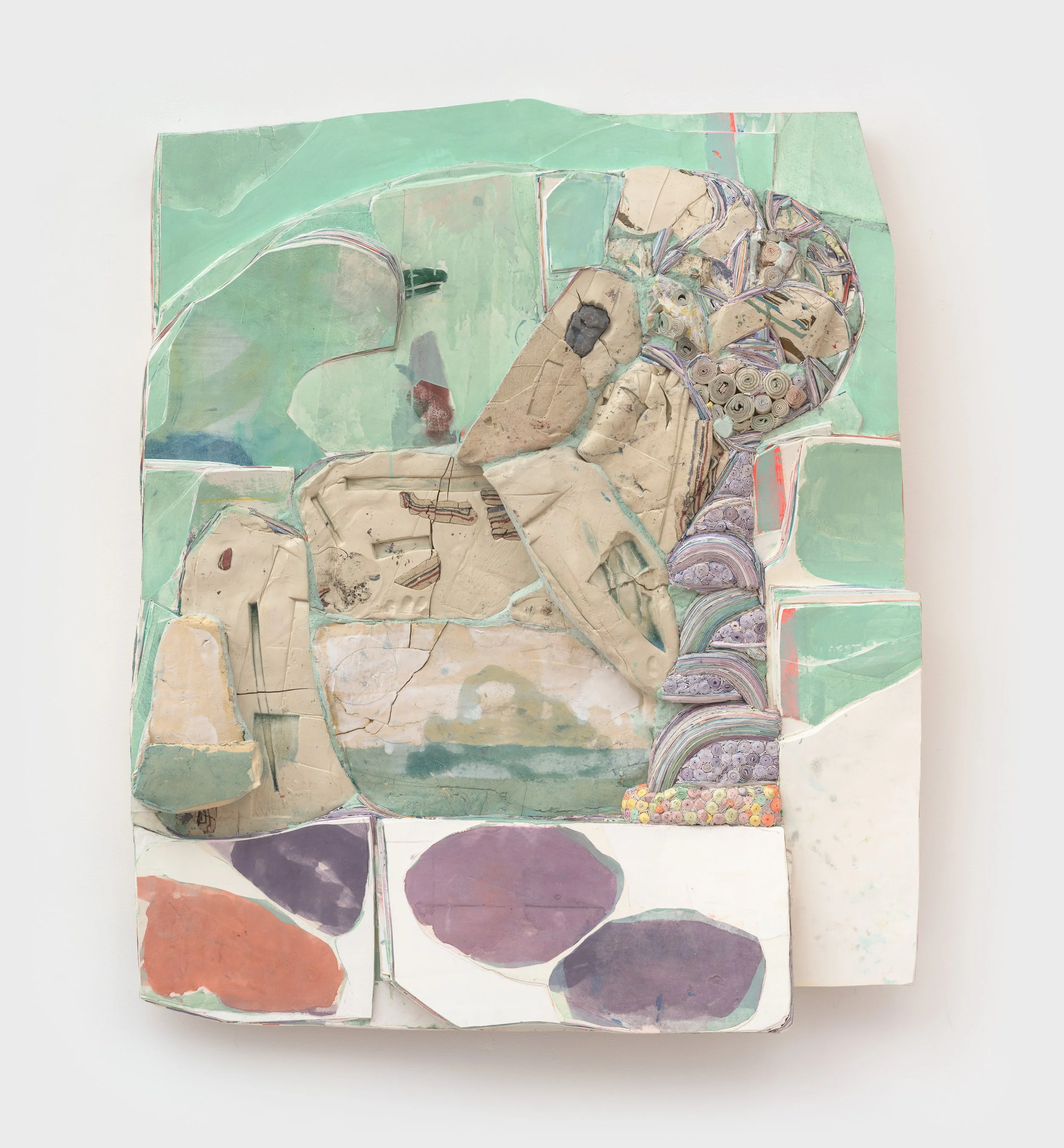

Hilary Harnischfeger St. Francis, 2026 paper, ink, dye, pigment, mica, hydrostone, ceramic, wood, glass 54 x 44 x 5 1/2 in(137.2 x 111.8 x 14 cm)

L: Do you have any expectations for the viewers when engaging with your work? Is viewing your work in the same manner as the slow processes of the natural world something you would like viewers to be mindful of?

H: I don’t have expectations for viewers, but I hope they allow themselves time and curiosity when engaging with the work. Because the pieces result from slow, repeated gestures as well as more violent, destructive actions—chiseling, hacking, and cutting—the surface carries both accumulation and rupture. I’d like viewers to notice the tension between these processes, almost like observing the rhythms of the natural world, where growth and erosion coexist.

Experiencing the work slowly can reveal subtleties that are easy to miss at first glance: the layering of marks, the play of light through perforations, shifts in color via absorption, material leaching and texture, and the traces of both gentle and forceful movement. I hope viewers can sense both the duration and presence, feeling the work unfold in time rather than consuming it all at once.

Hilary Harnischfeger Palo Duro, 2025 paper, ink, dye, mica, hydrostone, ceramic, wood 27 x 23 x 9 in (68.6 x 58.4 x 22.9 cm)

L: Have you ever encountered any conceptual challenges while trying to convey ideas of geological formations and transformations? If so, what challenges were those?

H: One of the biggest challenges has been suggesting geological transformations without creating a literal scientific model. I’m more interested in evoking the sense of accumulation, erosion, and layered pressure over time.

At the same time, I’m also mining the emotional and psychological dimensions of landscape—how memory and experience might shape and scar us, like natural forces shape physical matter. To make these processes legible at a human scale, I focus on traces of physical labor—layering, perforation, chiseling, and excavation—which mirror both natural and emotional forces. The work becomes a terrain of transformation, where time, impact, and emotional weathering are visible without necessarily needing literal representation.

Hilary Harnischfeger Violets, 2024 paper, ink, dye, mica, hydrostone, ceramic 8 3/4 x 12 1/2 x 10 in (22.2 x 31.8 x 25.4 cm)

L: Spending an extensive amount of time on each sculpture, you describe yourself as having a ‘relationship’ with each work. Do you carry a sense of responsibility in art marking?

H: Spending so much time with each sculpture has made me aware of their idiosyncrasies. Some are more needy, asking for coaxing and care, while others are stubborn or standoffish, resisting my attempts. Working with paper, clay, minerals, and plaster over the years has taught me to listen—to know when to be patient and when to act decisively. These tensions mirror the processes I explore: accumulation, fracture, and transformation. Over time, the works become collaborators, recording both physical and emotional engagement and revealing their own distinct rhythms and demands.

Hilary Harnischfeger Ron champ, 2026 paper, ink, dye, mica, hydrostone, ceramic, apophyllite 23 x 19 1/2 x 11 in (58.4 x 49.5 x 27.9 cm)

L: Repetition and time are the defining principles of your process. Do you feel that your work relates directly to your life?

H: Absolutely. Repetition and time in my work mirror the rhythms of my own life—its routines, patterns, and interruptions. Spending hours layering, cutting, chiseling, or marking surfaces becomes a way of marking experience, memory, presence, and loss. In that sense, the work is deeply personal: it carries traces of my physical labor, emotional rhythms, and attention over time. Each piece is like a record of both the external landscape I respond to and the internal landscape I carry with me.

L: What does the exhibition title Songs for Clouds mean?

H: The title Songs for Clouds reflects impermanence, movement, and perspectival shifts. Like clouds, the work can be experienced up close—where individual marks, surface planes, and tensions are visible—or from afar, where broader forms and relationships emerge. I’ve also aimed to allow more space in the pieces, creating breathing room within dense surfaces. The “songs” are gestures and interventions that record both physical labor and emotional presence, inviting viewers to read multiple meanings. The title suggests a dialogue between the ephemeral and the tangible, and between human action and natural forces.

The magazine featured Hilary’s exhibition, which is available here. For more information about Hilary’s work and her current exhibition at Uffner & Liu, please visit their site here.