In Conversation with Daniel Kukla

Courtesy of the Artist.

Daniel Kukla (b. 1983) is a visual artist whose work spans installation, sculpture, video, and image-making. Kukla's work has been exhibited at Aperture Foundation, The International Center of Photography, The National Art Gallery of the Bahamas, RISD Museum of Art, Masin Museo de Art de Sinaloa, Williams College Museum of Art, among others. His work has been featured in the New Yorker Magazine, The New York Times, Time Magazine, Wall Street Journal, Wallpaper Magazine, Juxtapoz, Granta Magazine, Guernica Magazine, The Washington Post, and others. Kukla is a graduate of the International Center of Photography’s program in Documentary Photography and Photojournalism. Prior to his photographic education, he attended the University of Toronto and received an Honours Bachelors of Science in Biology and Evolutionary Ecology.

RENATA: Your exhibition grapples with the aesthetics of containment—pins, specimen cards, photographic stillness—and their dual role in revelation and erasure. How do you approach these materials and forms in a way that resists the traditional authority of the archive or museum display? Several works in the exhibition involve physically altering the photographic surface—folding, piercing, burning, and embedding materials like black coral. What drives this material intervention, and how do you see it shifting the image from a site of documentation to one of embodiment or transformation?

DANIEL: I’m drawn to those tools of containment because they’re meant to organize and explain, but they also freeze things that were once alive. I like working with those forms in a way that looks to their history but also pushes against it—altering the surface, distressing the materials, highlighting the decay. I try to sit in the space between trying to preserve something and watching it fall apart. The moiré photogram sculptures are a good example—they reference pinned specimens, but the prints are unfixed, burned, folded, and pierced, so instead of feeling stable or scientific, they are constantly physically changing as if they are resisting being pinned down.

Moirée 2 (red blue), 2025 Marbled acrylic on chromogenic photogram (unique), found gorgonian, felt. 15 x 8 x 10.5”

R: The sculptural work made of marbled hog intestine is both arresting and unexpected. Can you speak to the significance of using this particular material, especially considering its historical role in preservation, and how it functions within the context of this show?

D: Yes, it’s a material that catches people off guard. Hog casing has this long history tied to preservation—it’s been used to hold and contain, especially in food preparation. In this show, I’m using it almost as a stand-in for skin or soft tissue—something fragile and organic. What’s interesting is how the marbling transforms it—something that’s usually seen as raw and commonplace becomes strangely beautiful. The swirling patterns echo the marbled endpapers of early scientific folios and natural history books, which adds this unexpected layer of reference. And because the marbling is unpredictable, each form feels unique and fluid- anything but orderly. It plays into that larger theme of resisting containment and the work itself hard to classify.

Installation view: Daniel Kukla: Thanatosis (Playing Dead), The Empty Circle Gallery, New York, 2025.

R: Thanatosis, or playing dead, is a natural survival strategy. How does this idea resonate within your broader practice, especially when considering your background in biology and interest in extinction, preservation, and absence?

D: Thanatosis, or playing dead, is such a strange mix of strategy and vulnerability, and that tension runs through a lot of my work. With a background in biology, I’m drawn to how things adapt, disappear, or leave only traces behind. That space between presence and absence feels really familiar. And as a queer person, the idea of blending in—or going still as a form of self-protection—has personal weight too. It’s a way to survive, but it also speaks to what gets erased or overlooked in the process.

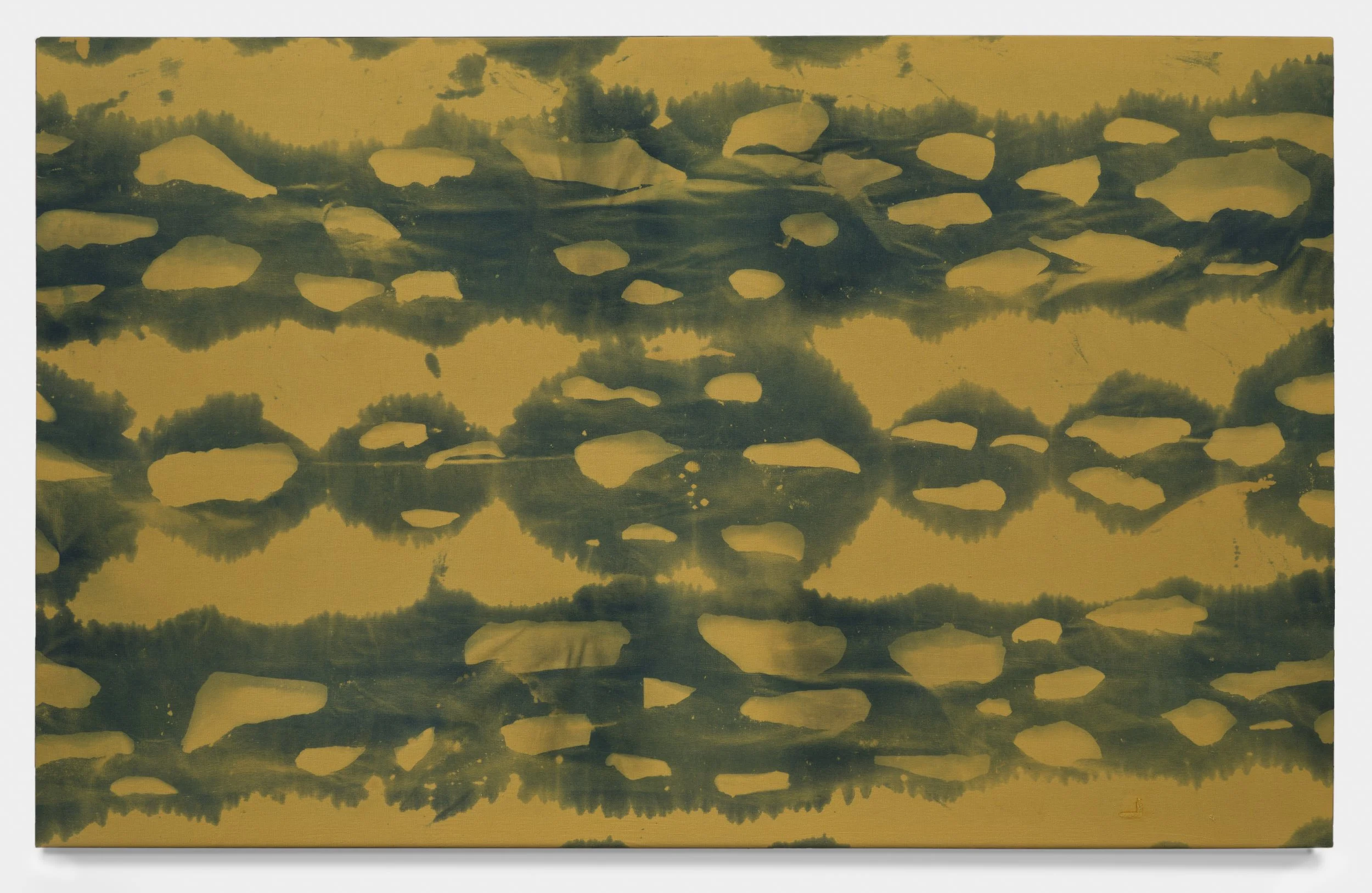

Field Log on Found Blanket, 2025 Cyanotype on cotton cloth. 52 x 84”

R: In your cyanotype made on a found blanket, stones act as masks to register presence through absence. How does this piece, and your use of elemental processes more broadly, expand your exploration of memory, indexicality, and the natural world?

D: For me, understanding the process is a big part of understanding the piece. The cyanotype on the blanket was made by gathering stones from the same ground the blanket was laid on. I placed them on the surface at night and covered them with a tarp. The next morning, I pulled the tarp away and let the sun expose the image. The stones acted as masks, so what you see is the imprint of their absence. The blanket itself had a former life—it was discarded, overlooked, almost playing dead in a way. By working with it, I transformed it and imbued it with new meaning. It’s a quiet, elemental process—just light, time, and material—but it holds a lot. It speaks to indexicality—how a mark or impression can stand in for something that’s gone. It becomes a kind of soft archive, not about control or classification, but about noticing. In the end, it’s an impression of the landscape—its weight, its shape, its memory.

R: You’ve described the archive, the specimen, and the image as “charged sites where systems of observation collide with acts of disappearance.” Could you expand on how this collision shapes your thinking and making, particularly when working with materials that inherently decay or degrade over time?

D: I think there’s something really charged about working with things that are meant to preserve—like archives, specimens, photographs—but knowing that they’re also always in some stage of breaking down. That tension shapes a lot of how I think and make. I’m drawn to materials that don’t last—organic matter, unstable surfaces—because they reflect the fragility of everything in life. So much of collecting or documenting is about control, about fixing something in place. But the reality is, everything degrades. The damask butterflies in the show speak to that directly—they are pinned specimens, but they’re laser-cut and etched with Victorian wallpaper patterns. That pattern isn’t random—those decorative damasks were popular at the same time as the Victorian natural history collecting craze, so the two histories are literally layered into the object. They blend the decorative and the archival, the domestic and the scientific, and the very act of marking them makes them even more fragile. It’s that mix of precision and impermanence that drives much of what I’m trying to explore.

Daniel Kukla, Damask 2, 2025 (detail). Etched assorted butterflies, entomology pins, glass, copper, silicone. Courtesy of the artist and The Empty Circle Gallery, New York.

R: Paper marbling appears repeatedly in the exhibition, not only as a technique but also as a conceptual metaphor for resisting fixed classification. What drew you to this process, and how do you see it dialoguing with the more rigid or taxonomic visual languages you critique?

D: I was drawn to marbling because it resists repetition—no two patterns are the same. It’s fluid and unpredictable, the opposite of taxonomic systems built on order and control. In the show, it acts as both a visual element and a metaphor for resisting fixed classification—letting things stay unsettled, unstable, and hard to pin down.

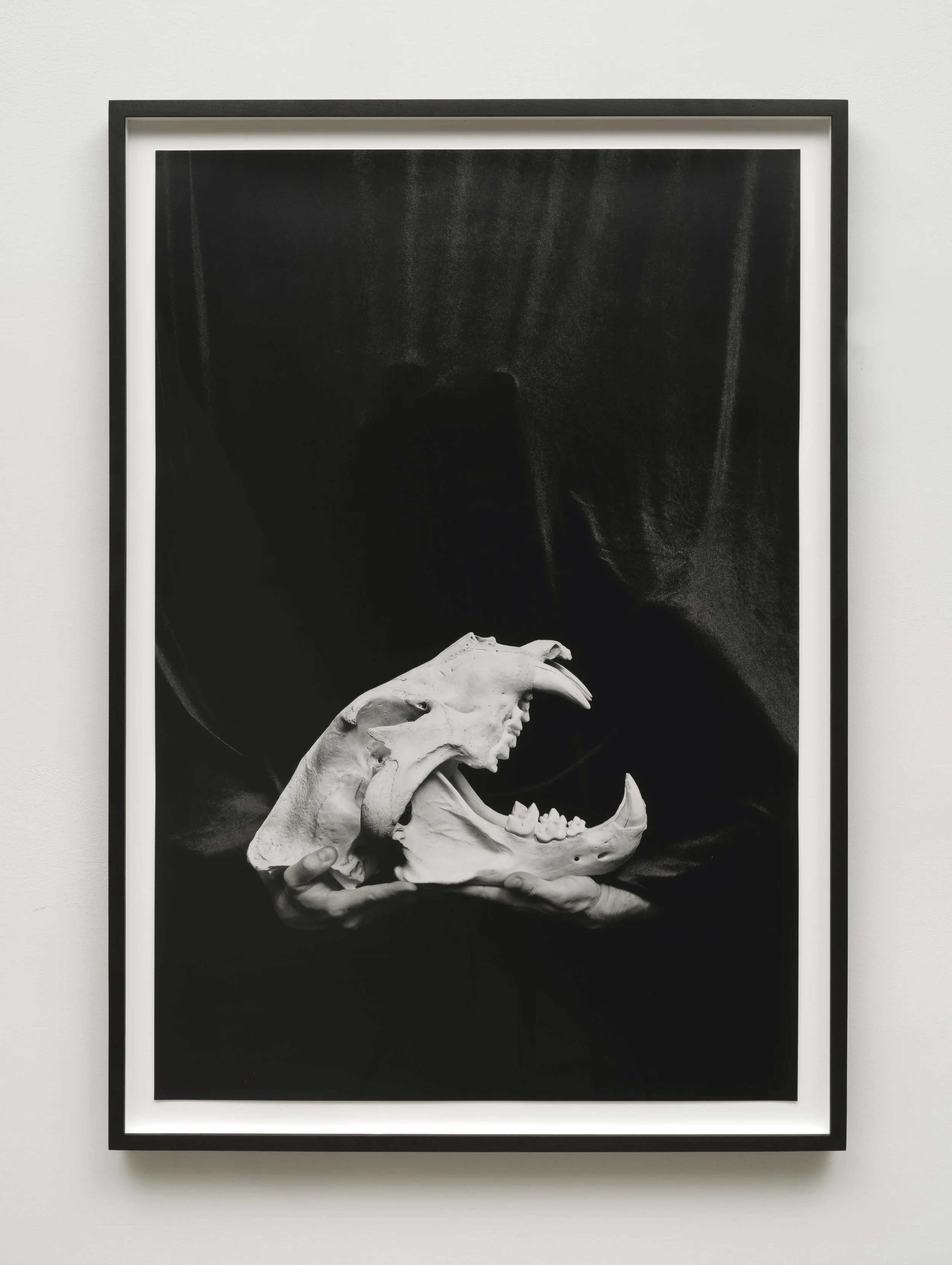

R: In the haunting self-portrait where you cradle a Siberian tiger’s skull while cloaked in velvet, you complicate the relationship between subject and object. Can you talk about how you navigate self-representation in this work, especially within the framework of authority, visibility, and power?

D: That piece plays with the tension between being the observer and the observed. Holding the tiger’s skull puts me in this strange position—part caretaker, part specimen. The velvet cloak is reminiscent of portraiture and museum display, but also feels like a disguise or shield. The skull itself is incredibly beautiful, and there’s a real desire to honor it—to acknowledge the life it once held. The image gives the skull a new kind of presence, perhaps a second life. It’s a self-portrait, but also a reflection on how we aestheticize death, how we hold on, and what we choose to see.

Siberian Tiger (Self-portrait), 2025 C-print, Fuji Crystal Archive print. 30 x 20” Framed: 32.5 x 22.5” Edition of 3 + 1 AP

For more information about Daniel’s work, please visit his site here, and he can also be found on Instagram. The magazine did a showcase of his latest exhibition which can be found here.