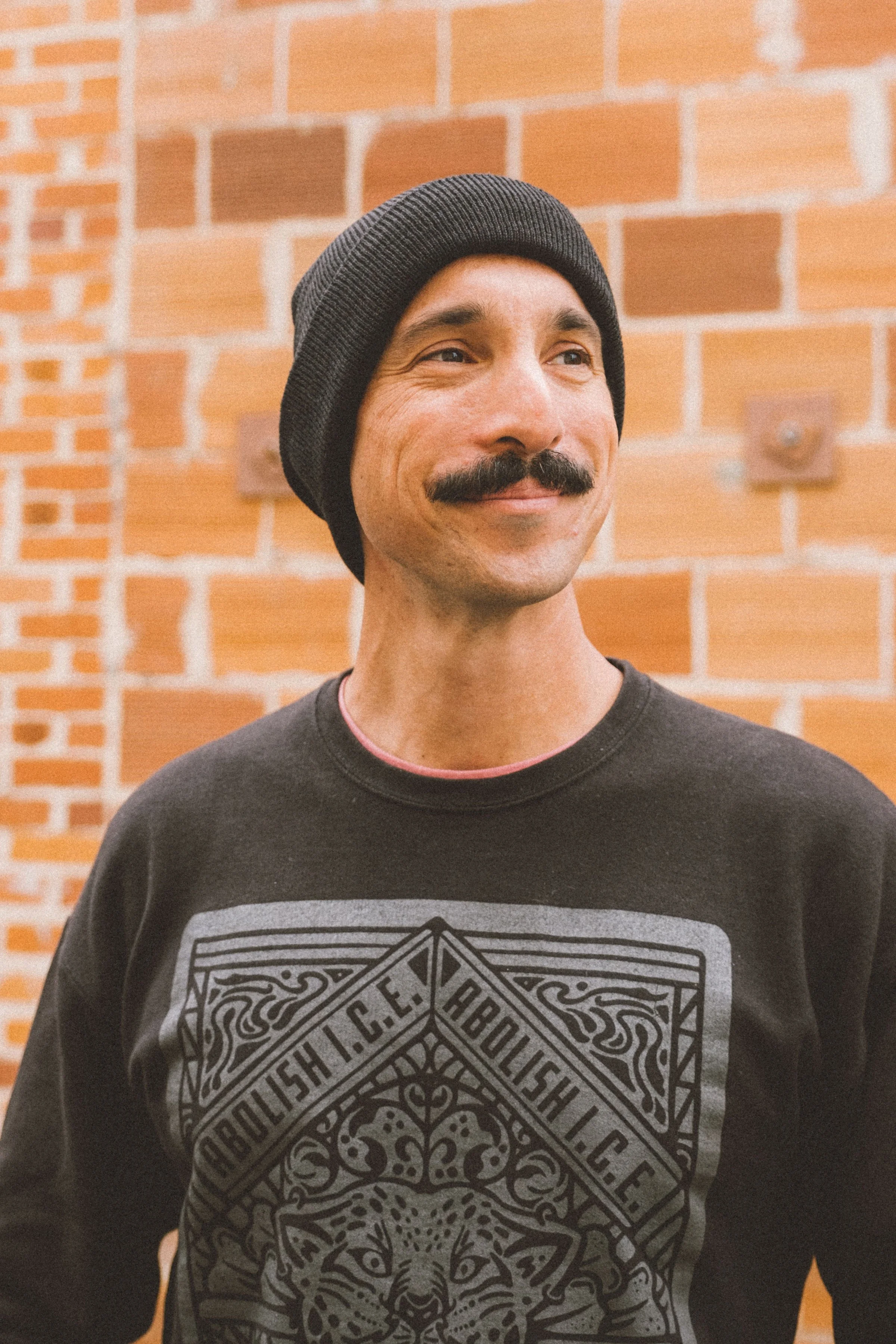

In Conversation Kevin Foote

Photo Credit: Courtsey of Artist

Kevin Foote (he/him) is a writer, teacher, and explorer. He was born and raised on The Central Coast of California, but now calls Green Mountain his home. When he’s not in class with his students, he loves investigating restaurants in the Denver region, trail running, and inviting friends and followers into the writing process online and in poetry slams. Kevin’s first collection, Cabin Pressure, is a work full of the woe and wonder of teaching, the unsung moments of victory in mental health struggles, and the unabashed joy of experiencing the natural world along The Front Range.

UZOMAH: What is it about poetry that gives it a unique expressive power, setting it apart from other writing mediums?

KEVIN: I am forced to say so much, with so little. I am in a line of work [as an educator] where it’s easy to overtalk or to overdirect or overinstruct, over-scaffold, over-model. It’s, it’s a world of words, in writing and auditory commands to manage behaviors that we modify in the name of student needs. When we’re in tune with best practices, we nail that balance. I’m sure most folks can think of teachers they’ve had who used words to fill airtime or worse yet, subjugate a room to their will for 50 minutes. I can only hope readers can think of at least one teacher who did the opposite; guided by best practices, speaking just when it was right, and that series of words filled the room with life and nurtured.

Poetry, like that teacher (I see you, Ms. Boone, Ms. Dixon, Mr. Pearce!) nurtures.

What I love about poetry is it forces folks like myself to follow through with those best practices in the most vulnerable and creative ways. It forces folks like me to pause, stop, and really think about what one line needs: Am I trying to convey an idea in a word, in five, in a line break? What am I really trying to get out, when everything else is removed? I think there is nothing more powerful than that. Poetry forces all of us to really assess and reflect on what we are trying to say, based on how in tune we are with what we are actually feeling. It's honest.

U: What makes for a powerful line or stanza in a poem?

K: That visceral connection within the reader. Something is conveyed that is felt in the gut, or behind the eyes, something that makes a belly laugh or makes you feel sick and you gotta stand up and go for a walk before picking up the book.

It doesn’t mean it has to speak directly into the reader's life. I think it’s really problematic, especially in so much spoken word poetry that ends up in slam scenarios, for writers to feel that they must just have, basically, an open blog, like early 2000’s style Julie & Julia vibes with some lyrical rhythmic element or clever wordplay to mask over how very stream-of-consciousness and unfinished the work is. I’ve been there, I’ve seen it, I’ve learned to write past that. We are not writing fiction, but we are also more than the sum of our own immediate experiences. Readers deserve, most importantly, to think independently and critically on what they just took in, without it spelled out in snappy language on the mic.

The poem doesn’t have to be about me. It doesn’t have to do anything with me. I believe my strongest writing, both in and out of this work [Cabin Pressure] goes beyond what I experience, who I am, the hyper-personal. While almost always rooted in me, the most powerful stanzas and lines demand the reader to experience something more important than the author.

A good line or stanza connects to the reader, bringing them into a place they’ve never wrestled with or even conceived, or, if it does in fact feel "very them”, they are forced to face those similarities in a new way, and that's the beauty of it.

U: How do you think poetry can explore an experience or convey the way an emotion feels and in a rare way that other types of writing cannot?

K: Poetry’s strength is how entrenched in imagery and entrenched in what is figurative, which makes what is in fact really happening feel unsettlingly important. I’ll expand more on this in the later question about mental health. For now, I think there’s a lot of power in what I’m doing in Cabin Pressure and I think it’s a great way for folks to engage not only their own experiences and emotions but those of folks they’d otherwise overlook. You don’t need to be an instructional educator, to be like, a classroom teacher, yet this work will make you feel it. You don’t need to know the minutia and the tiny things that happen in a day-to-day bell schedule, but you could feel what is really woven through that bell, that symbol–the emotions of fear and longing and desperation and hope and bittersweetness–those are things you feel as a human that are hard to digest but we must. Poetry is my tool to convey those shared emotions. I think that’s a good way of putting it: poetry is my tool to grab the reader and bring them into the world I exist in, that they may never experience ever, or vaguely remember as a student themselves.

U: Cabin Pressure is your upcoming poetry collection being published by South Broadway Press. What was the selection process like for each poem? What is the overall theme of the collection?

K: I think the biggest thing to remember with the selection process–if there is a new writer or prospective writer out there wondering what it’s like–think about backwards mapping. That's the term I would use. You approach a unit from the end goal, the cumulative task, the major essay, the presentation in front of parents at a conference, whatever it is you have to start at the end and work your way back. So, when I was ready to present this to South Broadway Press, I started with that mindset. When the book is closed, when the reader gets behind the wheel, or is wiping down the counter at the bar they tend, when they’re sitting in the pews at a church, and they’re processing what they’ve just read, what do I want for them, like, what is their takeaway? What task did I execute? Why?

The opposite would be spam-sending on Submittable with your “best” work. Maybe it matches the description you saw on social media calls or a submissions page, but where was your head at? Who’d you really have in mind when you clicked that button?

One of the takeaways for me when I looked at this and I wanted to see it come alive in print, was the simple guiding question I was quietly fighting to answer when this work began: What is a life well lived? The process of selecting poems then, was anchored in that question. If the end goal I backwards-mapped was “I want to show folks what a teacher’s life is like” or, “I want to show what my life as a teacher has been like”, I think the book would not have been picked, as was the case with earlier versions submitted to other publishers before I really checked myself on that guiding question.

U: If you could get any poet to provide you with notes on your poems and even edit your poems, who would it be and why?

K: I do not follow poets I do not know nor run into at community events, save for the late Andrea Gibson. I do not care about someone’s pedigree, nor acclaim. Part of this stems from over a decade of PD (professional development) where the “next big thing” is presented by so-and-so who is–surprise–such a big thing right now…and at the end of the day I remember nothing they told us, or I do in fact try to implement their suggestions with fidelity and it makes no difference, or, I find a better way by my own intuition.

Who do I want to provide notes and feedback and event edits to work? Those folks work with me every damn week. They are my friends. They are people who understand my intent and in love with rigor, can then step into the spot of edits if need be: Brice and Deb at South Broadway Press. Marissa and James at Twenty Bellows. Tyler at South Broadway Press and formally Beyond the Veil Press. Becca, Nic, Meg, Maple, it would be a litany of folks who I respect as writers who have put in the work, some through academic & distinguished training, others through sheer will and joy. These are people who have looked at my work and objectively given advice, as well as subjectively invited themselves into knowing who I am as a real person on the other side of the screen or microphone and met me where I needed actual improvement as a team member in the community of poets here, not as a subordinate or a random applicant on on a submission form who paid a fee. If you can find folks like that as a writer, you’ll be nearly unstoppable.

U: Can writing serve as a therapeutic tool when navigating mental health struggles? How have you personally used writing to cope with such issues?

K: Yes, a thousand times, yes. To anyone who actually knows me, I know that this book is hard to read. To those who have heard some of it on the mic, it’s hard to listen to, as this book was in one sense my way out of that well, out of that deep dark. This book hits directly on issues of suicide, ideation, depression, fatalism, nihilism, feeling institutionally overpowered, overwhelmed and left behind. Mental health is woven through many different cycles and seasons of this work, and I would only hope that writing can be that kind of tool for others. I know it was for me. The process of writing poetry has literally saved my life, and I am thriving because of what I learned of myself alongside professional academic therapy. The two enrich each other. Poetry serves as a mental health coping tool, I think, because it helps you separate yourself from what you’re feeling in the moment compared to what the ego is falsely trying to imprint upon you as what’s actually happening in that moment. Figurative language helps me distance myself from trauma creatively, not pretend it's not there or false, but I can assess it and understand better when it's placed in the figurative realm. I am seeing myself, and crucial moments in life, anew.

U: How would you explain poetry slams and what to expect to someone who has never experienced a poetry slam event?

K: I can’t speak for poetry events outside of the Denver Metro, but the ones that I’ve experienced since being here, oh maybe three years ago, are inviting and fun. Go, go, go!

[chuckling on the phone] I was really blown away by some random YouTube ad about a year ago, trying to get folks to move to Denver. Mountain bikers and people sipping cocktails by Platte were overshadowed by the cringiest voiceover, who was doing, like, a mock-poem that was clearly supposed to sound like a slam poem when you think of stereotypes of slam poems: Someone is going through a rap that doesn’t, I don’t know, maybe rhyme, it has that very forced jerky-staccato-scatting-wannabe rhythm to it. Overly assertive, obnoxiously dominant. I would assume the narrator’s name is Chad or Colin, and they also have an IKON pass and have dabbled in Joe Rogan listening. Never saw it again. It was a bombardment to me and I couldn’t help but laugh at it because people don’t do that shit here. People see through it. People support authenticity and honesty.

When I’ve gone to events at Lady Justice Brewing, Mutiny Information Cafe, Gold spot, or Townhall Collaborative, just to name a few who have supported me for years, there’s an actual community of writers. Other venues like The Pearl host competitions and pump up the energy that way. Other events like Punketry, have a live band experiment behind your poems in real time. Some events feel more like a reflective and calm live book reading. In all cases, there’s joy and support. People clapping and cheering or snapping, or doing that “mmm” sound. At one spot, someone shouted out bring that line back to the new poet on the mic, which I must admit, I do not like, because it makes me think of evangelical cult-ish responsorial tactics from my past, but I understood in the moment why they yelled that out: they were helping the newcomer understand they’re not only heard, they are appreciated, they are remembered. They smiled, they repeated the line slower, people responded with cheers.

You can engage or disengage [at the events] as much as you want but don’t talk over folks on the mic if you’re indoors. If you’ve ever been to an open mic for music, imagine that, but instead of it being white noise, it is the only noise you should be paying attention to when someone touches the mic. The speaker who is being brave and vulnerable hopefully for everyone there to witness.

U: What is your favorite thing about teaching and engaging with your followers via social media?

K: I grew up in a world where pastors were given this special attention for this mesmerizing yet so conveniently comfortable message they must deliver every Sunday morning before you go get your Starbucks or Krispy Kreme and football. That’s not reality. That’s how cults function. I am not your comfy Sunday.

For me, it’s been just a blast to kind of remove the curtain. I think that’s the word. I’m looking forward to reminding folks I’m no wizard. This is messy, clunky, and you’re invited to see it. You can DM me your complaints. You can unfollow me. You can watch my writing refine itself with me, ‘cuz, it’s me!

It is something that then demands engagement demands. Someone acknowledges my existence and dignity as a human who is vulnerable enough to show something creative.

As a writer, it helps me then look at myself like an athlete would and reflect on best practices, as mentioned earlier: Where did that line break maybe need to happen? What is my intonation like? Do I accidentally rush this line? Why did I slow down here?How would this look on a page versus in front of the reverse camera on an iPhone? It’s transparent and educational.

U: What do you hope readers will take away from reading your poetry?

K: I hope they take a step towards a life well-lived, by stepping into the brutal honesty of what it means to be human in front of children five days a week. I hope they will have bigger hearts, more open minds, they will slow down, they will speed up. They will be more in tune with what they need to do. When I look at what an educator does, it informs how I look at what’s happening in Gaza, when I look at what a teacher does, it informs how I treat my queer siblings. When I look at what a teacher does, it informs my voting, it informs my relationships and my mental health. I hope they take away the most uncomfortable and most protected parts of themselves and imagine what it’d do in front of children who are counting on them for fifty minutes, then ask themselves where do they go from there.

U: How do you decide the structure and form for a poem? Do you just free write, or do you set aside time to construct what you have in mind? Could you go through your process of crafting a poem, from the initial idea to the final draft?

K: The way it began when I was at my lowest point and trying to literally use poetry to differentiate between what was real and what is pulling me away from what is real based on fear, those trauma responses, my ego’s over reaction to those moments. I was simply writing it on my phone, on a piece of paper in the copy room, a student’s empty assignment crumpled on the ground, a piece of toilet paper one time when I didn’t want to leave the bar. Free write as a form of survival.

As I became re-centered, I had this 20 minute routine where I would sit in my bath before bed, cold bubble bath almost always. I would just type on my phone for 20 minutes. I would then think of spacing and punctuation and syntax, inner rhyme, wordplay, what have you. I tried to carve out that time to convey it in a way that was distant from myself, and attention to structure helps with that. I am not a metaphor. I’m not a simile or personification. This line is, that line is, and I can go to a writer’s workshop or swing by a poet friend’s house and discuss it. These were spaces where I could safely play with form and structure but they never felt like assignments. I wasn’t mimicking others, I was learning with them and then finding a structure that actually feels and reads and sounds like my voice, best.

At poetry readings, folks would start filming me. As mentioned in the question before, I used this time to assess the writing and the presentation side by side, just like athletes or students on my speech and debate team do. Go back to the document, that journal page, that line, see if you actually put the words where it makes sense. For folks who maybe come from my background–the heavily churched background–where you’re on stage and you’re speaking to people but you don’t have formal training provided, I’d have someone else read my poem. Take away the charisma and voice and stage blocking, and what does the reader actually experience? This has really helped me not get too set in stylistic choices, while keeping my voice. It also has kept me from inadvertently trying to measure my worth to other’s structures and styles. I look at Cabin pressure and I am proud, and more importantly, I am curious about myself and ready to grow.

For more information about Kevin’s upcoming title from Cabin Pressure, please visit the site here. You can see his published poems and works in progress on @feastsonfoote