In Conversation Esiri Erheriene-Essi

Esiri Erheriene-Essi (1982) is a United Kingdom-born and Amsterdam-based Nigerian artist from Lewisham, South London. In 2000 she attended Camberwell College of Art for a foundation year. From 2001-2004 she studied Media Studies at University of East London and attained a Masters of Fine Art from the same university in 2006. In 2007 Erheriene-Essi attended the international residency programme De Ateliers in Amsterdam, the Netherlands and in 2009 she won the prestigious Dutch Royal Award for Modern Painting prize. In 2011 she was a nominee for the Volkskrant Visual Arts Prize, and in 2014 Erheriene-Essi had her first museum solo exhibition at Museum Arnhem, the Netherlands. In 2019 she was shortlisted for the Prix de Rome, the oldest and most generous prize for talented artists and architects in the Netherlands.

UZOMAH: As an artist, you often depict experiences that resonate with the black experience and the African diaspora. How do these experiences, including your own, mirror those of individuals in the United States? And how does your art effectively convey these perspectives?

ESIRI: Even though my personal experience as a Nigerian woman in Europe is different in its specifics, the threads that connect me to Black people in the U.S. — and across the African diaspora — run deep. Whether you grow up in Lagos, London, or Los Angeles, there’s a shared sense of navigating identities shaped by migration, colonial histories, systemic racism, and cultural resilience. Those are realities that transcend borders, and they come through in my work because they live in my body and my stories.

When I make paintings, I draw on those common emotional landscapes — the joy in our cultures, the ache of displacement, the beauty of our traditions, and the need to reclaim our narratives. My colours, textures, and symbols often speak a visual language that someone in Chicago or New York might recognise just as easily as someone in Yaoundé would. Even if the specifics — like language, accent, or place — are different, the underlying spirit of resistance, creativity, and self-definition is something that connects us.

To make these experiences tangible in my work, I employ narrative approaches by blending personal stories (like family photos or oral histories) and speculative fiction, along with broader cultural references in hope of creating both intimacy and universality. Ultimately, my goal is to create paintings that feel both personal and expansive. I want my paintings to invite viewers in to recognise their own connections, whether that’s through shared cultural memory or through a deeper understanding of the Black experience and its richness and complexity. That’s why I put so much care into creating images that evoke these feelings. By bringing together visual elements rooted in my Nigerian background — West African patterns, bold hues, cultural symbols — and layering them with universal themes of Black identity and belonging, I hope my paintings becomes a bridge. It’s my way of saying: we see each other. Our histories may be different, but they rhyme. And in sharing those experiences honestly and vividly, my work aims to reflect back to people, especially across the diaspora, that they’re not alone. We are connected.

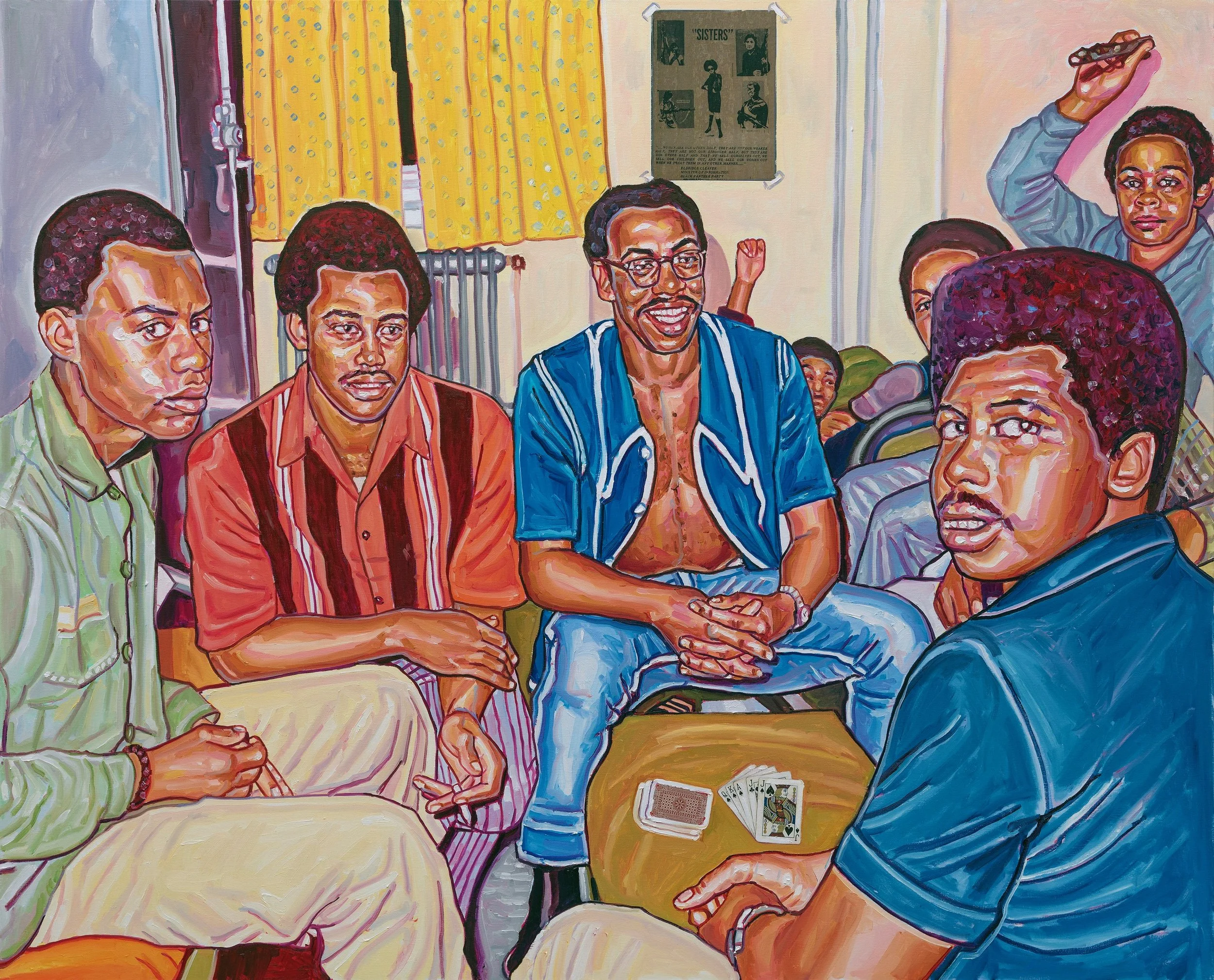

A Royal Flush (2025), 155 x 195 cm / 61 x 76.77”, oil, ink and xerox transfer on linen

U: When it comes to colour selection, what is your unique approach to capturing the diverse aspects of what it means to be black?

E: Over the years I have built up a vast archive of primarily instamatic snapshots from the 1950s to the 1980s, that I use as source material for my paintings. During this period photography became cheaper and readily available to a broader population, leading to a more diverse representation of histories being

documented. My works are full of depictions of ordinary moments, they champion and chronicle Black experience by exploring untold, often forgotten and even neglected narratives of people of the African diaspora. As a painter I am tickled by the distinctive colour scheme of these old photos, saturated and faded at the same time. The fascination with the colours is painfully ironic, considering the racial bias inherent in the technology of colour photography film and other colour film technologies which struggled to accurately reproduce darker skin tones, often resulting in a loss of detail and a washed-out appearance. Mostly because the cooler film emulsions at the time were primarily designed for

capturing white skin tones only and lacked the necessary sensitivity to reproduce the full range of melanin levels present in darker skin. So I use a vast range of colour in my paintings as a way to make up for what was denied.

When I choose colours to paint with, I’m very intentional about creating a visual language that celebrates the richness, complexity, and vibrancy of Blackness. For me, colour is more than aesthetic — it’s emotional, cultural, and historical. Due to my Urhobo Nigerian background, I’m drawn to the bold palettes you see in traditional fabrics like Ankara and Aso-oke — deep indigos, rich red, oranges, emeralds, and yellows — because they speak to my heritage and the way colour has always been a part of our storytelling. But beyond that, I also embrace softer, subtler tones — warm browns, velvety mahoganies, cool blues and glowing ambers — that reflect the full range of Black skin, beauty, and depth.

That contrast between bold and subtle lets me capture the many facets of what it means to be Black: we can be loud and joyful, or quiet and contemplative; we can hold pain and power at the same time. I often layer these hues so they interact and shift depending on the light — just like our identities do. Colour becomes a way of honouring every shade, every mood, every nuance. My goal is for anyone looking at my work to recognise a part of themselves in it — whether it’s their complexion, their mood, or their spirit — and to feel celebrated by the vibrancy and complexity of the palette.

U: How does colorism influence your artistic choices, and why is it still a significant and constraining factor for black communities?

E: I’m deeply aware of how colourism shapes both the personal and collective experiences our communities. Colourism in art, life and media is a very real issue. We constantly see the erasure of dark skinned Black women too many times.

In my paintings I want to celebrate and champion Blackness in figurative painting in multiple and myriad ways using only our collective gaze. Our histories, stories, cultures, the various hues of our beautiful skin, and our joy. I use a spectrum of colours to render skin tones in my figures and portraits,

emphasising the beauty and diversity of Black skin. Both as a celebration and a corrective: an affirmation that our various hues of dark skin is beautiful and worthy of reverence, even in societies that have historically devalued it.

And while I do sometimes incorporate photographs into my paintings as xerox prints that speak of the historical roots of racism, bleaching and colourism, such as references to colonial legacies (advertising, literature and cinema) and how these hierarchies continue to echo today. Joy and life from our point of view is always central.

Tomorrow is a long long time (2025), 138 x 195 cm /54.33 x 76.77”, oil, ink and xerox transfer on linen

U: Your current exhibition at Night Gallery, entitled Reflections, just opened. How do you develop and create the exhibition’s themes? Who are some of the visual artists and writers who have influenced you the most, and how?

E: The paintings in Reflections explore the subtle ways memory endures—through remembering, forgetting, recollecting, reassembling, and speculating. Photographs, incomplete stories, and fragments of memory become vessels that hold the essence of our histories in tangible form. I started the first painting towards the end of 2023 just after finding out I was pregnant with my second child, and thus I gravitated towards images centred around family, kinship and community. I was interested in how we shape and are shaped by each other within the diaspora and how the legacies of the people who came before us are forever entwined and influence our present and future. As I grew life, I thought of how history, family and ancestors will shape my children When I’m creating a body of work like this, I often start with fragments — photographs, personal memories, even colours or patterns that remind me of home. From there, I build a visual vocabulary around those elements. It’s very organic; I’ll sketch, collage, and paint until I see a thread that connects all of the pieces together into a story.

In terms of influences, my biggest inspirations have been artists who embrace identity and complexity without compromise. Writers like Toni Morrison and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie taught me to honour my voice and my history — they show me what it looks like to center Black women’s experiences with honesty and power. Visually, I relate to Kerry James Marshall and Robert Rauschenberg in different but equally meaningful ways — they both give me permission to embrace complexity in my practice.With Kerry James Marshall, it’s his deep commitment to Blackness that really resonates with me. The way he centers Black figures in every sense — physically, emotionally, historically — and renders them with power and dignity reminds me of my own desire to celebrate real Black people and our stories. His use of colour, scale, and composition insists that our presence is worthy of grandeur and nuance. I appreciate that so much, especially as a Nigerian woman creating work that explores diaspora identities. It feels like he’s opening a visual space where we can fully exist. And then with Robert Rauschenberg, it’s his fearless use of layering and mixed materials that speaks to me. The way he built meaning through the juxtaposition of disparate images, objects, and textures reminds me of my own process — assembling fragments of personal and cultural history into one unified whole. Rauschenberg’s openness to experiment and embrace chance is very freeing. It mirrors my interest in layering stories, memories, and visual traditions so they speak to one another and reflect the complexity of what it means to move between worlds. Both artists inspire me to honour the depth of my own experience — Kerry through his bold, celebratory presence of Blackness and Rauschenberg through his embrace of process and collage as a way of telling multifaceted stories. Together, they encourage me to make work that is truthful, layered, and alive. That’s the energy I strive for in Reflections — creating pieces that feel personal and specific, yet universal at the same time. Other visual artists and writers that have influenced me the most include Flora Nwapa, Grace Jones, Marlene Dumas, Octavia Butler, Stuart Hall, Henry Taylor, Roland Barthes, Faith Ringgold, Angela Wynter, Wangari Mathenge, Jacques Derrida, Gwendolyn Brooks, Kurt Vonnegut, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Jack Kerouac, Buchi Emecheta, Zora Neale Hurston, bell hooks, Astrid Roemer, Irenosen Okojie, Mickalene Thomas, Chinua Achebe.

The Reunion (2024), 137.5 x 195 cm / 54.13 x 76.77”, Oil on linen

U: Your paintings, as an archive of your thoughts and questions about history, are a valuable contribution to the understanding of the past. Could you share more about why you find it important to use art as a tool for historical exploration?

E: From as far back as I can remember, I have always been interested in images and history. As a child my mother would take me to the library and we would sit for hours as I poured over encyclopaedias and old newspaper clippings of my area in south London. I was intrigued by the past, how images of St Paul’s cathedral surrounded by bombed buildings and Piccadilly Circus in the 1930s differed to the early 90s version in full colour. And when I started painting I saw that art can serve as a bridge between the past and the present, offering uniquely personal and interpretive lens through which to examine history. My history as a British born Nigerian wasn’t in any of my history books at school, in fact according to that history we didn’t exist until the 60s and 70s when England invited immigrants from commonwealth countries to come ‘rebuild the mother country’. I saw a lot of gaps and silences in the limited history I was presented through eduction to the much more inspiring history I was fed from my grandparents and their generation that would tell me about their experiences, their interactions with ‘history’. I’m interested more in speculative history writing the past and the present, evoking empathy and understanding, opening up dialogues about past events in ways that conventional history books or academic papers might not. I see my paintings as living and interpreting vessels that can highlight the layers and contradictions within history, showing how it is not a static record but a dynamic process of remembering and reinterpreting. By creating paintings that engage with historical themes, I’m embracing the ambiguity found in the silences, the gaps and the uncertainties and suggesting multiple interpretations. I invite viewers to reflect on their own relationships with the past and memory by encouraging them to question what they see and know. It’s a space for curiosity, critical inquiry and reflection. The paintings in Reflections are a collection of love letters to the Black diaspora. An homage to our histories and a retelling of our ancestors’ legacies. It is a celebration of community and solidarity, a recognition that we are here because they were there. These works do not seek to amend history, but rather to center our gaze and reveal what has always been present. When I paint, I’m creating an archive that acknowledges those overlooked stories and feelings. It’s my way of engaging with history on a personal level — weaving together family memories, cultural symbolism, and historical fragments — so that they live on in a form that can be seen, felt, and revisited. Painting allows me to imagine what might have been forgotten, to speculate on what was never written down, and to ask questions that wouldn’t necessarily fit into a traditional textbook. That process feels especially important as someone who carries the histories of the African and Black diaspora. It’s not just about looking back; it’s also about reclaiming these histories and preserving them for the future — for my children, for my community. Every brushstroke is a way of saying, “We were here. Our stories matter.” In that sense, art becomes a kind of living record — one that invites people to reflect, connect, and remember alongside me.

U: Being based in Amsterdam, how do you incorporate your vivid themes of being Nigerian? How has your experience been since moving to Amsterdam? How would you describe it?

E: Amsterdam is this melting pot of cultures, so my Nigerian identity is always vivid and alive in my work. Whether it’s in my colour choices, the way I tell stories, or how I dress, I’m always infusing elements that remind me of ‘home’ — Ankara patterns, traditional motifs, vintage magazines and advertising or even just that bold, unapologetic energy that’s so Nigerian.

Moving to Amsterdam was definitely an adjustment. Amsterdam is more reserved and structured compared to the vibrancy and spontaneity of London and Nigerian culture there. But that contrast has been a really powerful part of my creative process. It’s given me this balance between freedom and focus.

Sometimes it feels like I’m bringing a splash of Warri or Lagos into a very orderly European canvas — and I love that. My experience here has been one of growth, exploration, and creating bridges between my Nigerian roots and my new surroundings.

Everything I do comes from being Nigerian. I may have been born in London, but my parents, community, and experiences stem from being Urhobo.

When You Were Young (Sweet Sixteen) (2025), 145 x 181 cm / 57 x 71.25”, oil, ink and xerox transfer on linen

U: What are you currently reading, if anything? Do any authors stick out to you as influences?

E: I’m recently finished reading ‘Kindred’ by Octavia Butler. The last time I read it was my first year of university when I was 18 and taking a science fiction course.

The idea of time travelling between the past and the present was something Octavia, Toni Morrison and my primary school teacher Barbara Johnson gave me as a tool in my work. I’ve always been unsatisfied with canonical, bleached history, and I like the idea of being able to speculate and contribute to the gaps in historical sequence. Before that I read all the books in the detective Harry Bosch series by Michael Connelly in preparation for visiting LA. The books are very cinematic and specific to Los Angeles and wider California.

Right now I’m reading Freshwater by Akwaeke Emezi — it’s so vivid, raw, and fearless in its exploration of identity, gender, and spirituality. Emezi’s voice is unlike anyone else’s, and as a Nigerian, seeing those cultural elements and myths woven into a contemporary story feels really powerful to me.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is another huge influence — her work gave me permission to embrace my own complexity and speak unapologetically as a Nigerian woman. Writers like Taiye Selasi and Nnedi Okorafor also inspire me because they bridge worlds so seamlessly, showing how tradition and modernity can coexist. They remind me that my story doesn’t have to fit into a narrow box — it can be expansive, bold, and completely my own.Toni Morrison’s concept of “rememory” from Beloved (which I read yearly) is incredibly powerful to me — it’s one of those ideas that has stayed with me long after I first encountered it. Morrison writes about rememory as this way that the past is never really gone; it lives in places, in people, and in our bodies. It’s not just personal, it’s communal — especially for Black people and the African diaspora — because we carry so much history, trauma, joy, and resilience with us across generations.

As a Nigerian woman making art in Amsterdam, I feel that rememory every day. Even though I’m far from home, I can feel my ancestors, my culture, my lineage in my hands when I create. Morrison reminds me that these histories don’t disappear just because we change locations or live in different times. They’re present — sometimes vividly, sometimes subtly — and they shape who we are and what we make.

And that’s why rememory is so important. It validates our past, even the painful parts, and allows us to weave those pieces into our present stories. Morrison showed us that we don’t need permission to reclaim those memories — they already live within us. That’s a really liberating thought for me, both as an artist and as a Black woman.

The Icing on the Cake (2025), 127 x 169 cm / 50 x 66.53”, ink and xerox transfer on linen

U: How did you choose art as the medium through which you express yourself?

E: I’ve always been drawing since I can remember and really into literature, so I only ever wanted to be an artist or a writer. I fell in love with Jean-Michel Basquiat when I was 13 after my art teacher at the time gave me a book on him. It wasn’t until I was 16 bored out of my mind on a school trip to Tate Britain that I walked by a painting by Lucian Freud ‘girl in a striped dress’, and recoiled in awe, fascination and anger at how beautiful I found the work. The next day my mama gave me £20 to buy his monograph at the bookstore. And the day after that I hounded my art teacher to tell me how to use oil paint. And 26 years later I’m still obsessed with oil paint.

Art felt like the most natural way for me to speak, even before I had the words for my thoughts and emotions. Growing up I was surrounded by so much color, pattern, rhythm — it was in the food, the clothes, the music, even the way people told stories. Drawing, painting, and creating were how I could take all of that energy and make sense of my own voice.

And honestly, art allows me to be my most authentic self without limitation. It’s this beautiful, powerful space where I can explore my identity as a Black Nigerian woman and show the world my perspective — unapologetically. Whether I’m celebrating my culture, pushing back against stereotypes, or simply telling my own story, art is my way of making sure I’m heard.

A memory from your youth (London Trocadero) (2024), 135 x 135 cm / 53.54 x 53.54”, oil, ink and xerox transfer on linen

U: How can art change the stereotypes that are often damaging about Africans with the use of art in society?

E: Art has this unique ability to challenge harmful narratives because it reaches people on an emotional level. When Africans, especially African women, create and share our own stories through art, we take control of the way we’re seen. It’s no longer someone else telling a one-dimensional version of who we are.

By showing the richness, diversity, and beauty of our African cultures, histories, and people, we can break down those tired, damaging stereotypes — like the idea that Africa is one single place or that African women are passive or voiceless. Art celebrates our complexity: our strength, our creativity, our joy, even our struggles. It allows us to counter these harmful myths and replace them with truthful, multi-layered representations.

And beyond just visuals, art also sparks conversation — in galleries, in public spaces, and even online. Every time someone experiences a piece of art that reflects a more nuanced view of African people, it can shift their perspective. That’s the real power of art in society: it can change hearts and minds one story at a time.

Ultimately, I find that art can humanise the past, connecting us with historical experiences and perspectives in ways that foster deeper understanding and reflection.

For more information about Esiri’s artwork, please visit her site here. She can also be found on Instagram here. The magazine also did a showcase of her most recent exhibition at Night Gallery, which can be found here.