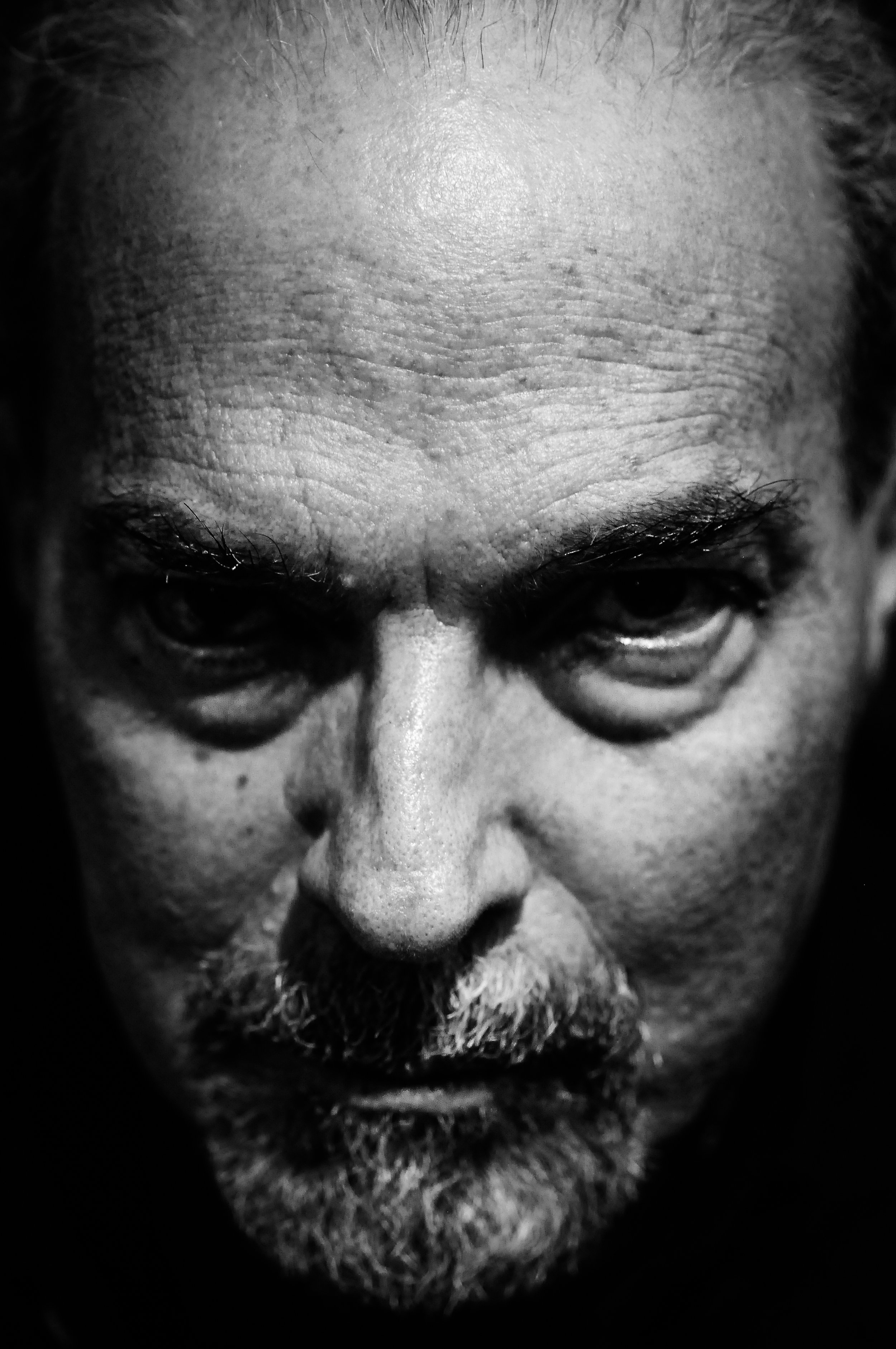

An Effervescent Conversation with Jack Burman

Photo Credit Ty Tonus-Burman

Jack Burman is a Canadian visual artist Since the mid-1980s, Jack Burman has been visiting concentration camps, medical laboratories, churches, and catacombs around the world looking for the dead who are still present among the living. He has exhibited widely across the world in places such as North America, Europe, and parts of Africa. His artwork has been exhibited in galleries and art spaces such as Le Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Pratt Manhattan Gallery, New York, Nicholas and Lee Begovich Gallery - California State University, Los Angeles, The Palace of Culture, Warsaw , The Arsenal/Le Mois de la Photo, Montréal, Humanorium, Montréal; Humanorium, Quebec City. His artwork is held in the permanent collections of The National Gallery of Canada, The Art Gallery of Ontario, The Image Centre (Toronto).

He is the author of several books, including scripta (Toronto: Andora, 2023) The Dead, Vol.I 2nd Edition (Toronto: Magenta Foundation, 2023) The Dead IV (Toronto: Andora, 2022), he walks he talks he / crawls on his belly like a reptile (Toronto: Andora, 2019) The Dead, Vol.III (Toronto: Andora, 2017), The Dead, Vol.II (Toronto: Andora, 2016), The Dead, Vol.I (Toronto: Magenta Foundation, 2010).

I had the pleasure of asking Jack about what lens he uses, how he came about taking photographs, and so much more.

UZOMAH: Why do you capture the dead and not the living?

JACK: I was marked for this work at a certain time in the past. Turned toward it. They are as many as the living. With a stillness, a fullness, edged and completed in blackness. It helps you to breathe.

U: How did you come about taking photographs?

J: On a day I don’t remember the date of. It was in the summer. Picked up a camera so the words could go through it and never appear again, or not as words. More days followed, and then more.

Courtesy of artist

U: Do any of the remaining family members of the persons you take photographs of have a problem with you exhibiting their loved ones?

J: No relative of any woman or man or child I have photographed has ever spoken to me. Once or twice in remote regions a morgue attendant or other official has asked me—on behalf of the family—to de-identify the place/time etc.

U: Most Native Americans felt that graves of any type should be left intact and found the practice of collecting human remains for study fundamentally repulsive. What are your thoughts on that and other cultures' views on how the death of human beings should be handled and discovered?

J: Some photograph the dead of wars. Some photograph the dead at crime scenes. Some photograph the dead of famines. Regardless of culture. I photograph the dead.

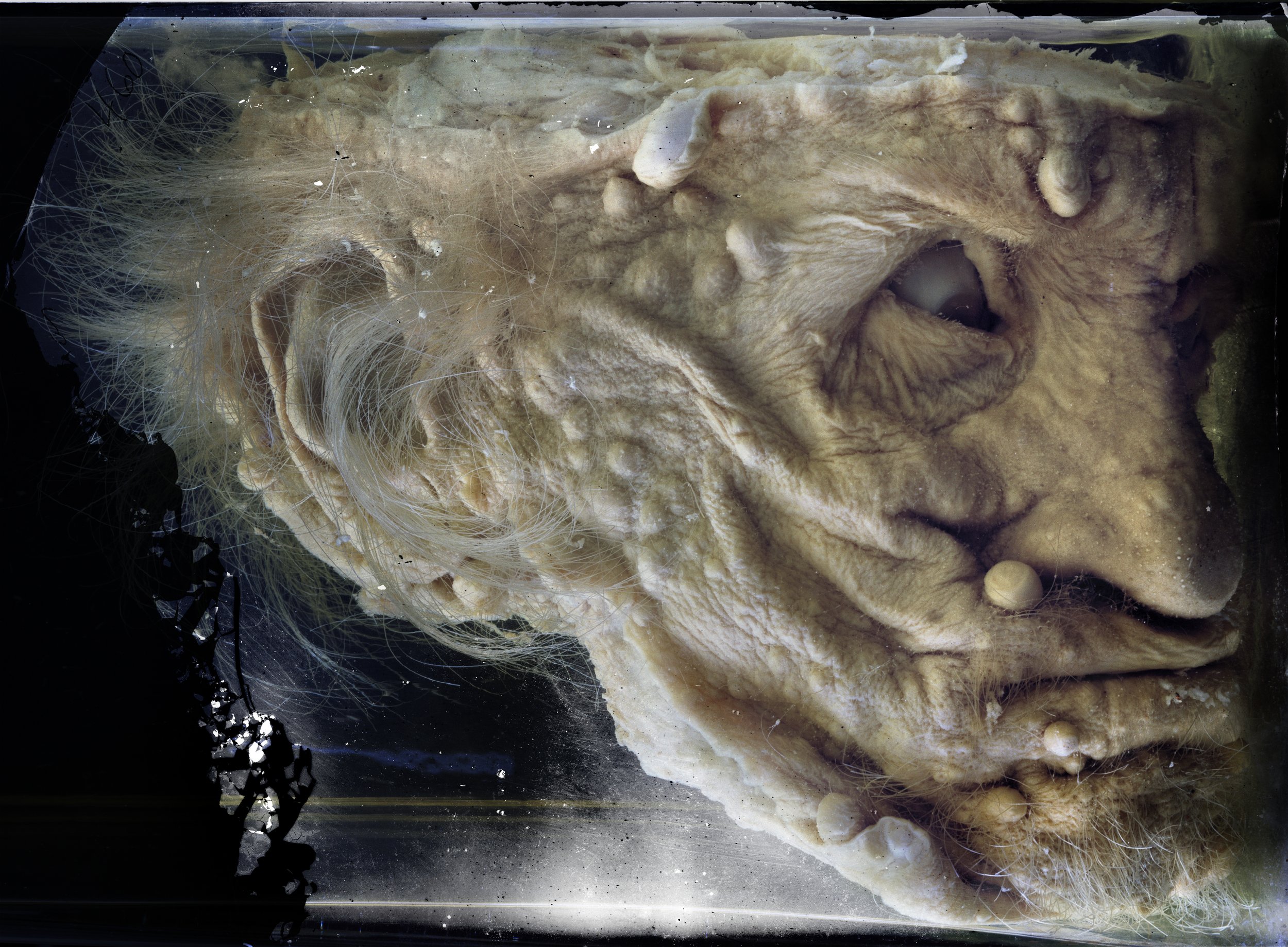

Courtesy of artist

U: What stories do you wish your photos would tell about the person the audience is viewing that maybe while they were living has not been described?

J: Around 1800 near a town in southwestern Germany an asylum inmate in his forties who had been in a catatonic crouch for thirteen years died. His crouching skeleton was preserved. Call that a “description” if you like. It isn’t. The photos tell stories of oblivion.

U: At what point does a set of remains cease being a person and become an artifact or, in your case, a work of art instead?

J: The head or body or hand of a person cannot cease being in front of the camera. What I make is not that being. It is a simulacrum—clear, hard, full—of that being and of my hands’ work. It is time—from five hundred years before, or from a few hours before—stopped, or slowed.

U: What is something you have learned about life being around the dead?

J: How to move from region to region to where they are. How to cross walls. How to change my face and voice. The price of blood and being.

U: Do you ever think you are disturbing the dead's spirits?

J: No. I cannot reach their death. They care nothing for me before I come to them and nothing after I go. I bring my spirit to the place where they are.

U: What kind of lens do you use?

J: With the 4x5: Schneider APO-SYMMAR 5.6/150

With the 8x10: Rodenstock Sironar-N 5.6/240

U: How do you use light to get the type of photo you desire to get the most out of the subject?

J: It is said that Caravaggio crushed a hole in the wall of his workroom so he had hard raking light coming from the upper left. I work with natural light coming from there—some of the time.

Courtesy of artist

U: You have traveled all over the world, visiting various sites. What do they most have in common other than a place of resting and the final days for people?

J: The anatomy and pathology departments smell of dust and formalin, nothing much else. The Catholic catacombs lust after fullness and over-fullness. The Andean cloud forest skies gyre with cold, roiling light. What do these have in common? They are on what Sebald called “the indistinct borderline with transcendency.”

U: In one sentence, how would you tell someone what you do and why?

J: It is done to reach the body, the hoar-finish of damage and clear light and loss, the cold burn of time laid on and under the skin.

For more information about Jack’s work please visit his website. You can also find him on Instagram.